|

|

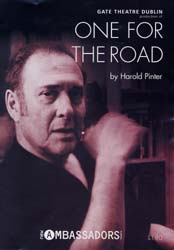

One For

The Road 2001 ACT

Productions & Gate Theatre, Dublin |

||||

| The Lincoln Center Festival section click here | ||||

Directed by Robin Lefevre Cast:

|

||||

The Daily Telegraph - Thurs. 5th July 2001

Harold Pinter wrote One for the Road (1984) after meeting two "extremely attractive and intelligent young Turkish women" at a party, who seemed casually indifferent to the use of torture in their country. "Instead of strangling them, I came back immediately, sat down and, it's true, out of rage started to write One for the Road," he told his biographer, Michael Billington. The play ended a painful, three-year period of writer's block for Pinter, and ushered in the explicitly political agenda of his later work. Last week, I was rude about two of Pinter's later political plays, Mountain Language and Ashes to Ashes at the Royal Court, describing them as sketchy, paranoid and self-righteous. In contrast, One for the Road, strikes me as a mesmerising, terrifying, brilliantly controlled piece, which distils the rage that inspired it into a flawless, richly resonant miniature masterpiece. It lasts only 30 minutes but haunts the imagination for hours after you have left the theatre. The added attraction of Robin Lefevre's production for Dublin's Gate Theatre is that it stars the playwright himself in the leading role as a state interrogator of an oppressive unnamed regime. Before he became a celebrated dramatist, Pinter was a lowly rep actor, playing such glamorous locations as Whitby, Huddersfield, Worthing and Palmers Green, but, after seeing him in several of his own plays, I'm convinced that, if he hadn't become a great writer, he would now be almost as famous as an actor. As well as having a tremendous stage presence and a wonderfully rich and resonant voice, Pinter brings out every nuance, every shard of black humour and every psychological quirk in the character of Nicolas, a self-proclaimed civilised man who earns his living as a torturer. What makes this play so much stronger than Pinter's subsequent political plays is that it retains the ambiguity of his greatest work. How can a man who behaves so vilely entertain and intrigue us so compellingly? There are even moments when you catch yourself feeling sorry for the bastard. Nicolas, who runs the sinister state institution where the action is set, and who proudly informs one of his victims that he has the ear of the "nice chap" who "runs the country", has brought in a whole family for questioning. The husband (Lloyd Hutchinson), presumably a dissident intellectual, has been tortured, his wife (Indira Varma) repeatedly raped. The fate of their delightful seven-year-old son (Rory Copus), who Nicolas sits on his knee, hangs horribly in the balance until the play's devastating final line. Yet Nicolas for the most part remains urbane and civilised, as if talking to guests at a house party. More disturbingly still, there is a strong sense that Nicolas is sexually attracted to both his almost mute adult victims and perhaps even the child. Not a word seems redundant in a series of tense, teasing dialogues between Nicolas and his three prisoners which fascinatingly suggest that the torturer is tortured himself, despite his smooth manner. He knocks back the whisky with alcoholic urgency, and, in a couple of moments when we see him alone, seems deeply perturbed. There is a sense of terrible loneliness, of a man who serves the state because he has nothing, and no one, else. His victims are his only friends. "Who would you rather be? You or me?" Nicolas asks the husband. It is the achievement of both Pinter the writer, and Pinter the actor, that we know, in the very core of our being, that there could be nothing worse than to be Nicolas. As well as offering a hideously persuasive account of the mechanics of psychological torture and the apparatus of state repression, One for the Road takes you right into the heart of one man's moral wasteland. Charles Spencer

The Guardian - Wednesday 4th July 2001 Pinter the writer is much lauded. Less is written about Pinter the actor. And watching him play the sadistic interrogator in his own short, shocking play about political oppression you realise he could have been a contender: mixing muscular authority with flickering irony he would have made a natural classical heavy. A pity, you feel, he never gave his Richard the Third. That quality of lethal surprise is necessary in One for the Road. In four brisk scenes we see Nicolas, a high-ranking state official, confronting three imprisoned members of a family: the silent, ultimately mutilated Victor, his raped wife Gila and their vulnerable son. The play has an incremental horror. But is needs shade and colour in the playing of Nicolas if it is not to seem a straightforward condemnation of state brutalism. In Robin Lefevre's Gate Theatre, Dublin, production, Pinter gives it remarkable variety of texture. In a long, silent prelude we see Nicolas psyching himself up for the ensuing ritual. With each of his victims he then assumes a mask of playfulness which gradually splits open to reveal the moral cruelty beneath. Pinter flashes his dentist's smile at Victor and rolls the word "insouciant" round his tongue as if it were a fine wine. To Victor's son he is dangerously avuncular and to his wife curiously sexual. But each time Pinter's fausse bonhomie suddenly snaps to reveal that this is a game being played to a deadly conclusion. Pinter's acting highlights the duality of linen-suited commissars like Nicolas. They may be vain, insecure and even, in a curious way, avid for validation from their victims. But deep down they are driven by implacable conviction. When Pinter talks of the "common heritage" from which Victor is excluded he instinctively bunches his left fist. And when he describes Gila's late father as "iron and gold" it is in tones of awestruck admiration. In his actions, Nicolas is clearly evil: the paradox is that he believes he is keeping the world clean for God. Pinter and Lefevre bring out this paradox to the full. Liz Ashcroft's set also implies that behind this banal state office lurks another shadowy world. And Lloyd Hutchinson as Victor, Indira Varma as Gila and Rory Copus as their son highlight the stranges paradox of all which is that this tortured family has some secret quality which not even their oppressor can understand. It would have been good to see the play teamed with A Kind of Alaska with which it will shortly appear in New York. But it offers an unforgettable image of tyranny and shows Pinter has that quality of danger that defines all the best actors. Michael Billington

The Financial Times -Thursday 12th July 2001

Pinter shows off his talent for menace Even to folk who have never seen one of his plays, Harold Pinter is famous for his views on foreign politics - in particular, for his views on tyranny, oppression, and the involvement of the world's leading nations in the politics of smaller nations. The twist is that Pinter - he's famous for this too - has a terrific knack for menace, heartlessness, authority. He has just given five performances in the lead role of his own One for the Road (1984) at the New Ambassadors Theatre. Only some 32 minutes long, this play - together with Mountain Language - shows most plainly his views on politics. It will now go on to the Lincoln Center Pinter Festival in New York. The scene is Nicolas's office. Nicolas - is he chief of police? Head of the secret service? - is a high-ranking authority in a country where the army overrules democracy and where torture, rape and murder are used against those who are deemed to be enemies of the state. In successive scenes Victor, his seven-year-old son Nicky, his wife Gila, and finally Victor again are brought to Nicolas's office. Nicolas does almost all the talking in every scene: urbane, suave, calmly self-righteous. Only as he goes on talking do you realise that this seemingly intelligent, apparently restrained figure is in fact virtually mindless, so corrupt in his own exercise of absolute power that his thoughts lack any seriousness. It is gradually implied that Gila has been successively raped and will be raped again; that Victor has been tortured and, before the final scene, has had his tongue mutilated; and that little Nicky between his appearance and the final scene has been killed. But these things make no serious impression on Nicolas's mind. He talks in a stream of consciousness that reveals all too much. Power, food, drink, sex, torture, death, power, God, self, death, power: his thoughts run around in their calm, appalling circles. You sense, beneath the assured surface, Nicolas's neediness, his weakness, his madness. It is Dublin's enterprising Gate Theatre that has produced this revival. Robin Lefevre, the director - he also directed the current Gate Homecoming, also set to visit New York this month - has elicited the best performance we have seen from Pinter in several years. His rhythm has more suspense than I have known before - Pinter the actor has sometimes been curiously fond of riding over those famous pauses that Pinter the author likes to write. His interpretation is full of compelling self-contradictions; the physical, tactile tenderness he shows to his victim Victor, the paternal jocularity he shows to little Nicky, the insulting tone in which he addresses Gila. This is a subtle account of the play. Line by line, you are held by the gradual, shifting self-revelation of Nicolas's mind. It is a far more complex understanding of police-state tyranny than that shown by such famous villains as Scarpia in Puccini's Tosca, and far more appalling. And, politics apart, you feel how Pinter can turn a stream of consciousness into the stuff of purest drama. Moment by moment, your understanding of the scene before you keeps being mysteriously and drastically changed, as if by sudden shafts of light from unexpected angles. Alastair Macaulay

|

||||

| Back to plays Main Page |