|

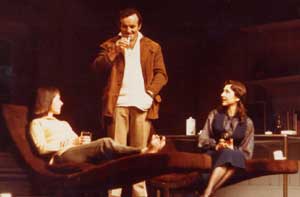

| Old Times - Premiere | |||

First produced by Royal Shakespeare Company at

the Aldwych Theatre, London, 1 June 1971 Deeley - Colin

Blakely Directed by

Peter Hall Settings and

Lighting - John Bury

Pinterís

New Pacemaker In a whitewashed

farmhouse somewhere by the sea, three people digest the casserole

they had for dinner and reminisce about the past. Anna, the guest,

once shared a flat with Deeleyís wife Kate, and rhapsodies nostalgically

about their innocent youth as London secretaries, going to concerts,

listening shyly in artistsí cafes, playing records of Gershwin and

Kern. Constrained but affable, Deeley joins her in a contest of

memory, singing off-key, antiphonal snatches of the songs of the

forties, while Kate smiles at them silently. Its familiar soil:

strangers trying to wrench a common ground of cliche from disparate

pasts. Then something goes wrong with the conversation. You have

a wonderful casseroleí says Anna, slightly too warmly. Deeley looks

baffled. ëIím so sorryí, she apologises, blushing and smiling at

her Freudian slip. ëI meant wife. You have a wonderful wife. She

was always a good cook. Sometimes we would make an enormous stew

for supper, gobble it up, and then, more often than not, sit up

half the night reading Yeats.í

Anyone with

an ear for Harold Pinterís dialogue will recognise the territory

on to which his new play Old Times, at the Aldwych, shifts

with those lines. A gauntlet has been thrown down. Battle is engaged.

The battleground is Kate: which of the two, Deeley or Anna, has

possessed more of her? The weapons, as usual, are sex and language:

the language of innuendo, cultural discomfiture, the slight verbal

excess staking an emotional claim. Truth has nothing to do with

it. ëMore often than notí? Really? The winner will be the one who

can impose his or her version of the past. Ana has made her opening

thrust. Kate cooks for Deeley. With her, she read poetry. Within the

same triangular frame of memory as Silence, it mixes the

sexual ambiguities of The Collection with the territorial

wars of dominance which underlay The Homecoming. Growth seems

a better word than advance. The techniques, the preoccupations are

the same. Thereís no new departure from the ground he has made his

own. But he mastery of it is more stunning than ever, the economy

even more perfect. Wonderfully taut, comic and ominous, Old Times

shows Pinter more and more himself and less like any other playwright

writing today. More clearly than before, it takes the form of a duel: a game of skill top the death. One after the other, the adversaries offer their blows to the body. Brutally, Deeley tells how he picked up Kate in a cinema showing ëOdd Man Outí, walked her home and bedded her. Anna listens smiling, with no more belief than Mick in The Caretaker gave to Daviesí story of his papers as Sidcup. Then it is her turn, and she has a double riposte. Funny how vividly you imagine what you think happened isnít it, whether it happened or not? She has a memory ñ is it real?- of a man who cried in Kateís bed. But of course it is unreal beside her memories of their life together: poring over the Sunday papers, rushing out to old films at suburban cinemas ñ like ëOdd Man Outí.

Itís like watching

a marvelous skilled game of cricket or tennis. What kind of ball

will they send over next? How will the receiver parry it? Deeley

has more crude power ñ he is Kateís husband, isnít he? ñ but he

flusters more easily, being Irish, and lacks Annaís patient finesse.

She has the authority of money and culture (a husband and villa

in Sicily, a velvet glove of good tempered gentility to mask her

steely determination), and Kateís vague, smiling passivity seems

to be on her side. But much as Pinter enjoys games, they arenít

what he writes about. As in The Homecoming, the final, devastating

victory belongs to neither battler, but to the woman battled over.

People are not prizes to be won in tournaments. They belong to themselves. Peter Hall

directs the comedy with a musicianís ear for the value of each word

and silence which exposes every layer of the text like the perspex

levels of a three-dimensional chess board. ëDo you drink brandy?í

asks Deeley. Vivien Merchantís pause before replying that she would

love some is just sufficient to remind you that, on Pinter territory,

every question is an attempt to control and every answer a swift

evasion. In the immaculate cast, she has the advantage of her long

mastery of Pinter idiom, from the deployment of hesitations down

to the crossing of strapped-over ankles. But in its way Dorothy

Tutinís silent Kate is as commanding a performance, and the surprise

if the evening is Colin Blakelyís Deeley: funny, desperate and individual

as his character roles at the National never fully revealed him. |

|||

| Back to plays Main Page |