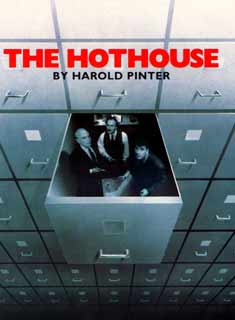

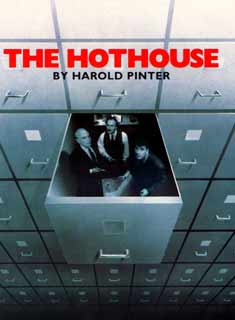

Harold Pinter and John Shrapnel

|

The Hothouse, Minerva Studio Theatre,

Chichester,

17 August - 9 September 1995, transferred to Comedy Theatre, London

September 1995

Roote - Harold Pinter

Gibbs - John Shrapnel

Lamb - Christien Anholt

Miss Cutts - Celia Imrie

Lush - Robert East

Tubb - Roland Oliver

Lobb - Peter Blythe

Directed by David Jones

Settings - Eileen Diss

Costume - Tom Rand

Lighting - Mick Hughes

Sound - Tom Lishman

Assistant Director - Joe Harmston

Give the man an exploding cigar

by Charles Spencer

Watching Harold Pinterís starring performance in his own play

The Hothouse, you realise that we lost a magnificent comic actor

when this former denizen of tatty reps transformed himself into

Britainís greatest living dramatist.

Programme Cover

|

The play itself reinforces the impression of recent

years that, although Pinterís pause-filled plays undoubtedly are

menacing, enigmatic, and all the other adjectives associated with

that handy word Pinteresque, he is, perhaps above all else, a wonderfully

funny writer.

I have a hunch that while he was establishing his reputation as

Ýan important dramatist,

Pinter and his directors deliberately played down his gift for gags,

concentrating instead on all that was murky, avant-garde and unsettling

in his work.

Which might be one reason why The Hothouse took so long to

see the light of day. He wrote it in 1958, shortly after The

Birthday Party, but then put it aside for more than 20 years

before giving his permission for a 1980 production at Hampstead,

which transferred to the West End.

Of course, this welcome revival has its serious side. It is set

in a sinister state institution, the precise function of which is

never quite explained. The inmates ñ whom we never meet - are described

as patients and referred to by numbers; thereís an interrogation

scene involving electrodes and white noise; and at the end we learn

that all the senior staff have been massacred by the residents.

It's impossible not to think of the psychiatric hospitals in which

totalitarian states lock up their dissidents.

Pinterís paranoid vision of malign government control had become

familiar to the point of clichÈ in the years since the play was

written. What keeps the piece fresh is edgy, brilliantly timed dialogue,

its confrontations between characters as they battle for territory

and control and its unashamed relish for jokes.

You may find this hard to credit, but in The Hothouse Pinter

works the old exploding cigar routine, not to mention a heroically

awful joke based on the phrase ëfor the love of Mikeí which might

give an end-of-the-pier comedian second thoughts.

Pinter himself is in glorious form as Colonel Roote, who runs the

institution. This bristly-moustached character ñ prone to sudden

intemperate rages, rather like the famously testy playwright himself

ñ is having a terrible Christmas Day. One of the inmates has died,

and another has given birth, with the suggestion that Roote might

be the father.

Basil Fawlty and Captain Mainwaring come to mind as Pinter blusters,

bullies, submits grotesquely to flattery and gradually lays bare

an authority figure that is losing control. The smiling menace with

which he inquires, ëBetween ourselves, man to man, youíre not by

any chance taking the old wee-wee out of me, are you?í is alone

worth the price of admission.

The supporting performances are impeccable. John Shrapnel is superb

as a blank-faced, creepy functionary; Celia Imrie is a slinky, smilingly

manipulative femme fatale; and Tony Haygarth is hilarious

as the insolent slob who rattles Roote.

David Jonesís production, ingeniously designed by Eileen Diss, never

relaxes its grip and there is a splendidly unsettling soundtrack

(Tom Lehman) featuring the whimpers and diabolical laughter of the

inmates.

Itís a memorable evening of menace-fuelled mirth, and Pinter, for

so long suspected of ingrained solemnity, must surely be a candidate

for the comedy performance of the year award.

The Daily Telegraph, 24th August 1995

Programme Cover - Comedy Theatre

|

Pinter ñ prince of comedy

by Ian Shuttleworth

One of the most remarkable things about seeing Harold Pinter act

in his own plays is that they generally brood much less when

he is around. The eloquent pauses and significant obliquenesses

are all in place, but Pinter understands the extent of the comedy

of his work.

Not that humour is difficult to spot in The Hothouse, which

he wrote in 1958 but ëset asideí until 1980, and now transfers from

Chichesterís Minerva Studio in David Jonesís fine production. The

shadows are all cast by the scheme of the play rather than its execution.

The setting of an undefined ërest homeí in which the inmates, known

only by numbers, are routinely abused and electronically tortured

by staff whilst the man in charge blusters inanely and his subordinates

jostle one another for the succession, offers pre-echoes of One

For The Road and Mountain Language. Yet the actual script

is less suggestive of Orwell or Kafka than of Orton.

As Roote, the ineffectual, pompous ëchiefí, Pinter sports both a

moustache and a manner reminiscent of Dadís Armyís Captain

Mainwaring. He makes an excellent self-important, retired colonel,

unable to string a sentence together at the best of times and gradually

subsiding into a whiskey haze while his accent becomes broader and

more plebeian.

Rooteís assistants, Giggs and Lush, are played with equal finesse

by John Shrapnel and Tony Haygarth. Shrapnel is a master of arid

assiduity, his face a careful blank but seemingly emitting a whir

of the turning cogs of a Machiavellian scheme. Haygarthís Lush is

sly, insinuating, greased with self-satisfaction as he riles his

superior, accusing him of impregnating patient 6459 and murdering

6457.

Lush is the agent of two moments of unimaginably broad un-Pinterian

comedy. Having twice had whiskey flung in his face for these allegations,

the third time he grabs Rooteís tumbler and twirls it above his

head in a galumphing balletic parody ñ later extracting Roote with

an exploding cigar. The mind boggles that Pinter ever wrote such

slap-stick, let alone between The Birthday Party and The

Caretaker.

As Miss Cutts, mistress of both Roote and Gibbs, Celia Imrie wears

a permanent cool smirk, obviously playing her own game throughout.

Christien Anholt is all naove idealism as Lamb, who is ultimately

sacrificed amid the electrodes of ënumber one interviewing roomí.

Even here the gags persist, as the disembodied voices of Gibbs and

Cutts hector him, ëHave you always been virgo intacta?í and ëWhat

is the law of the wolf pack?íThe play itself lacks a little polish:

introducing an entirely new character for the final five-minute

scene smells of dramatic desperation. In the end, though, its successes

are much more surprising than its flaws. On this occasion, Pinterís

famous ëweasel under the cocktail cabinetí is wearing a red nose

and clownís baggy trousers.

Financial Times, 5th October 1995

|